HIIA Analysis – Written by Ruslan Bortnik

The full analysis is available here.

The history of Ukraine is one big lesson on geopolitical fragility and the absence of effective security guarantees with enforcement mechanisms. Indeed, few countries know the curse of illusory security guarantees better than Ukraine. Ukraine gave up its nuclear arsenal in exchange for international assurances in 1994, not a ratified defense guarantee, which failed operationally in 2014 and strategically by 2022. Today, Ukraine is once again faced with the age-old question of security guarantees, recently voiced by U.S. Vice President J.D. Vance. How can Ukraine overcome the curse of security guarantees? Can it avoid another Budapest Memorandum-style trap? This study attempts to objectively understand the differences in traditional approaches to guaranteeing Ukraine’s security, the reasons for their failure now and in previous historical periods, and the most successful international practices and examples. The use of enforceable security guarantees to preserve Ukraine as a self-sufficient, strengthened, stable, neutral country—a compromise zone (a military-political and economic buffer) between the West and the East—would not be a shameful defeat or a temporary solution—it would be a victory for common sense and a humane approach to ending this terrible and dangerous war.

Ukraine’s Bitter Experience from the Budapest Memorandum to Today

No country’s modern history illustrates the perils of empty security assurances more than that of Ukraine. In 1994, Ukraine surrendered the world’s third-largest nuclear arsenal—inherited from the Soviet Union—in exchange for the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances. In the document, Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom “agreed to respect the independence and sovereignty and the existing borders of Ukraine” and “refrain from the threat or use of force” against the country. Kyiv also received promises of assistance if threatened or attacked with nuclear weapons. France and China later made separate statements about providing Ukraine with security guarantees in connection to its nuclear disarmament. Kazakhstan and Belarus signed similar memorandums with guarantors.

Crucially, though, these were not ironclad guarantees. U.S. negotiators deliberately avoided the word “guarantee,” which would have implied a binding commitment to use military force, and instead opted for the term “assurances.” And the document itself was never ratified by the parliaments of the participating countries, raising questions about its legal status. In essence, Ukraine received political promises in lieu of a defense treaty.

Tragically, those promises proved hollow. In 2014, Russia, one of the signatories, breached the memorandum by annexing Crimea and fomenting war in eastern Ukraine. The other guarantors, the United States and the United Kingdom, responded with diplomatic protest and sanctions but no military intervention, since they had never actually committed to defend Ukraine with force. The Budapest Memorandum, once touted as a milestone of post-Cold War peace, is now viewed as a cautionary tale—a failed assurance that left Ukraine dangerously exposed. Ukrainian officials have openly referred to it as a “failed 1994 security guarantee” and “strategic mistake” that Moscow exploited.

Ukraine’s subsequent attempts to secure its sovereignty only reinforced the lesson. After 2014, Ukraine’s parliament abandoned the country’s official non-aligned posture that had been codified in 2010 during the tenure of the Western-skeptical government of Viktor Yanukovych, precisely because non-aligned had “left Ukraine vulnerable to external aggression and pressure.” The law’s explanatory note cited Russia’s invasion as proof that the 2010 status failed to shield Ukraine, creating an urgent need for “more effective guarantees of independence, sovereignty, security, and territorial integrity.” In other words, Ukraine recognized that only concrete security alliances or commitments could deter further aggression—not vague neutrality. At the same time, the media and political figures both inside and outside Ukraine often confused (sometimes seemingly intentionally) “non-alignment” with “neutrality,” which Ukraine never had, since neutrality requires the existence of international treaty or other form of international recognition, which Ukraine never received.

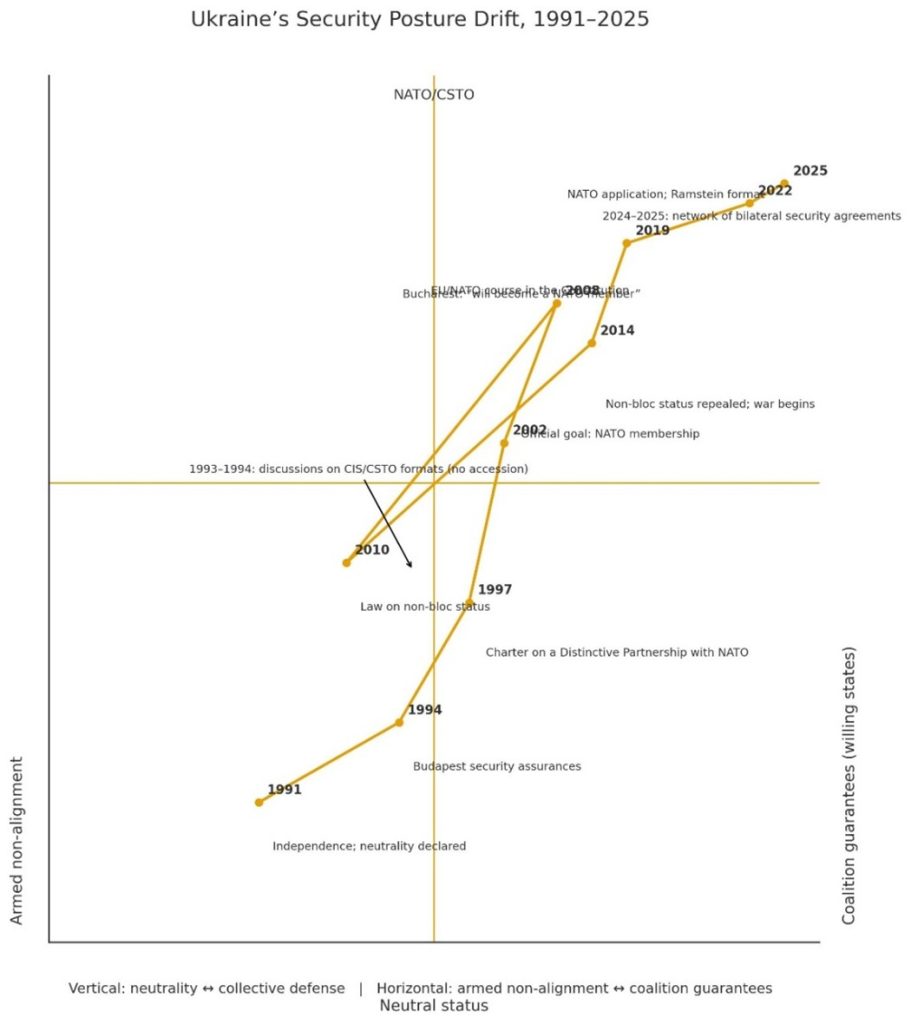

The entire political history of modern Ukraine is one of vacillations between non-alignment and attempts to integrate with the West by joining the EU and NATO. But despite the fact that political rhetoric and the legal framework have indeed undergone significant changes during this time, the country has essentially run in place, remaining non-aligned.

Figure 1. Ukraine’s Security Posture Drift, 1991–2025.

Ukraine’s problem is not merely one that emerged in the last century, however. Throughout Ukrainian history, security and collective defense agreements with Poland, Russia, Turkey, Sweden, Austria, and Germany were left unimplemented. Each time, the fate of the Ukrainian people and the state was decided, and each time, the outcome was not to their liking.

The Divergent Approaches of Major Powers to the War

U.S. policy toward the Ukraine war under President Donald Trump has markedly diverged from that of European allies and the previous U.S. policy of supporting eventual Ukrainian NATO membership and refusing to compromise with Russia. Since taking office in 2025, Trump has pressed for a rapid end to the conflict, even if it means Ukraine making painful concessions and has shown a willingness to negotiate toward Moscow. The White House has explicitly taken NATO membership for Ukraine off the table for now, signaling that Kyiv should give up hope of joining the alliance as part of a peace deal, and publicly put the onus on Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy to end the war as soon as possible by renouncing NATO aspirations and even territorial claims.

Meanwhile, there has been a shift in Washington’s material support to Ukraine. No new aid package has been approved in 2025. Trump froze all U.S. foreign assistance in January and moved to dismantle the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)—terminating or transferring dozens of aid programs benefitting Ukraine. Then, in March, the Trump administration temporarily paused ongoing shipments of military aid as well after a contentious meeting with Zelenskyy. This pullback has left Kyiv and NATO frontline states worried that American resolve is weakening despite continued Russian aggression.

President Donald Trump has stated many times that the United States would help guarantee Ukraine’s security in any future peace deal with Russia, while emphasizing that Europe will play the primary role in providing those guarantees. On August 19, 2025, Trump told President Zelenskiy, “When it comes to security, there’s going to be a lot of help … are a first line of defense because they’re there, but we’ll help them out.” Two days later, U.S. and European military chiefs presented security guarantee options to national security advisers, in which European countries would provide the most forces, with the United States leaving open the possibility of air support.

European leaders have responded to Trump’s approach with a mix of dismay and insistence. Key allies like France, Germany, Britain, Italy, Poland, and others have reaffirmed that they will continue backing Ukraine and sanctioning Russia until a “just and lasting” peace is achieved. This means European resistance to any deal that legitimizes Russia’s gains in Ukraine and a new balance of power in Europe. European leaders were alarmed when Trump, after meeting Russian President Vladimir Putin in Alaska, announced that going straight to a comprehensive peace settlement without even a ceasefire was the best way forward—a position “hitherto opposed by Kyiv and its European allies” but which Russia has maintained.

In a joint statement on August 16, European leaders affirmed that “Ukraine must have ironclad security guarantees to defend its territorial integrity”—with Europeans playing a primary role in their implementation. Governments have made clear they expect to provide the bulk of the military forces in any future scheme, deploying troops under their own national flags, not just under NATO. They also emphasize that Ukraine must be directly involved in defining who defends it “on the ground, in the air and at sea.” Europeans are wary of proposals that demand territorial concessions or allow Russia undue influence over Ukraine’s future, stressing that international borders must not change by force.

Europe is bracing for a future with diminished U.S. involvement: NATO states are boosting defense budgets to 3–5% of GDP and discussing ways to collectively protect Ukraine and Eastern Europe even if Washington retrenches. This includes initiatives such as a European-led “Coalition of the Willing” to aid Ukraine, and commitments by European NATO members to increase weapons production and training support for Ukrainian forces. In short, Europe’s approach diverges by doubling down on support for Kyiv and transatlantic unity, even as Trump questions U.S. obligations. European officials privately acknowledge they are often adopting a “reactive posture,” trying to mitigate Trump’s unpredictable moves.

Europeans recognize, however, that European forces would struggle to guarantee Ukraine peace without U.S. support. Their militaries lack certain capabilities that the United States brings to the table, such as long-range deterrence or nuclear backup. A European peacekeeping or “reassurance” force would require not only numbers but also the backing of American air power, strategic assets, and credible willingness to escalate—elements that Europe has difficulty furnishing alone. Ukraine also clearly understands this. Zelenskyy has commented on the issue, saying that “security guarantees without America are not real security guarantees.”

Russia’s approach, for its part, has been to retain control over any model of security guarantees for Ukraine. Russia also frequently raises the issue of European security and guarantees for Russia. The Kremlin continues to demand significant Ukrainian territory as part of a compromise, including areas that its military has not yet captured. President Putin has shown no signs of abandoning his maximalist goals; on the contrary, Russian troops have even launched new offensives amid the diplomatic turmoil.

Moscow has declared a conditional openness to U.S.-mediated security guarantees for Ukraine, however, as an alternative to NATO membership, which Trump’s envoy presented as a decisive concession on Putin’s part. This promise remains vague and, in Russia’s understanding, will return the parties to the state in April 2022, when the parties held talks in Istanbul, and Russia claimed a position as one of the guarantors of Ukraine’s security after the end of the war. Notably, the Kremlin categorically rejects any NATO troops on Ukrainian soil under a deal, which would prevent Ukraine from being included in the Western zone of influence. All of this suggests that Moscow’s ultimate goals have not changed—it seeks to dictate terms to Ukraine and consolidate its gains. Thus, the divergent positions of the major powers have created a precarious dynamic: Trump seeks a peace agreement, European allies seek to prevent a bad deal, and Russia and Ukraine seek victory either through negotiations or by continuing the war.

In short, since early 2025, Washington has downgraded the priority of Kyiv’s accession to NATO and signaled a compromise settlement, Europe has doubled down on its support for a protracted war to avoid a “bad peace,” and Moscow seeks terms that codify gains while rejecting NATO forces in Ukraine.

Lessons from History & Three Options for Ukraine

Not all security guarantees are created equal. History shows a stark difference in outcomes between legally binding defense commitments backed by force and non-binding assurances or neutrality pacts. The latter often prove hollow when tested. For example, due to a lack of enforcement power, the League of Nations’ collective security promises in the 1930s failed to stop acts of aggression such as Italy’s invasion of Abyssinia. Likewise, the 1939 guarantee made by Britain and France to defend Poland’s independence did not deter Nazi Germany’s attack—it only led to war after Poland had already been invaded. More recently, the 1975 Helsinki Final Act and other pan-European security principles like non-aggression and respect for borders have proved ineffective too.

Switzerland’s neutrality from 1815 and Belgium’s neutrality guaranteed by treaty in 1839–1914 are the most significant cases of security guarantees granted by a wide range of the most powerful countries in Europe. Austria’s permanent neutrality after 1955 was also internationally guaranteed by the Soviet Union and Western powers, allowing Austria to remain peaceful and sovereign during the Cold War. The neutrality of Sweden and Finland likewise shielded them from direct conflict, supported by strong national defense and tacit Western backing (although Finland eventually joined NATO in 2023, and Sweden became a member the following year). Still, the most enduring case is that of Switzerland, whose neutrality was recognized by the great powers in 1815. Combined with its own strong defense capabilities and strategic geography, Swiss neutrality has kept the country out of wars for over two centuries, making it the longest-lasting and most credible example of a neutral security guarantee.

The U.S.–Japan Security Treaty (1960) and the U.S.–South Korea Mutual Defense Treaty (1953) remain prime examples of successful security agreements without neutrality. Both involve permanent deployments of U.S. troops and the nuclear umbrella, which have successfully deterred major attacks for decades. Similarly, Israel’s security partnership with the United States—though not a formal defense treaty—provides overwhelming military support to the country and an implicit guarantee of survival, deterring adversaries since the 1970s.

The lesson is clear: Security guarantees work only when they are binding, enforceable, and recognized by all relevant powers on the relevant ground. With NATO membership effectively off the table in the near term—due in part to President Trump’s stance and in part objections from multiple other allies—policymakers are urgently debating concrete security guarantees that could protect Ukraine in the interim. Several options have emerged, each with their own advantages and pitfalls.

- Coalition Guarantee (An “Article 5-like” Security Pact, etc.)

In lieu of NATO membership, Western leaders are discussing a bespoke security guarantee for Ukraine modeled on Article 5. The idea gained traction after President Trump’s summit with Putin, where Russia indicated for the first that that it would be willing to accept NATO-style protections for Ukraine so long as Ukraine stays out of NATO. Following the summit, Trump announced the United States would be willing to help provide Article 5-like assurances as part of a peace deal. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen hailed this openness, emphasizing that a broad coalition of the willing is ready to contribute to such guarantees. In practice, a coalition guarantee could resemble a defense pact where a group of nations pledge military support if Ukraine is attacked again without offering full NATO membership.

Planning teams from Europe and the United States have begun meeting to outline the kinds of military support this would entail. NATO’s European heavyweights—France and the UK—have indicated they might even be willing to station forces inside Ukraine or extend a nuclear umbrella under a new alliance. The key details, however, remain undefined. President Trump himself has been non-committal regarding the U.S. security role, with officials admitting that it’s “unclear whether Trump had fully committed to such a guarantee” and that any binding U.S. pledge would be a major concession for him. Russia approves of a vague guarantee but flatly rejects any NATO troops on Ukrainian soil, likely limiting the deterrent value of such a scheme. President Zelenskyy has welcomed talk of an international guarantee but pointedly warned that “there are no details on how it will work,” and Ukraine insists any guarantees cannot be mere political promises and must function like NATO’s. In essence, the challenge is to design a pact strong enough to deter Moscow yet acceptable to all parties.

French President Emmanuel Macron has stressed that the substance of the guarantee matters more than the name—a peace plan must meaningfully bolster Ukraine’s security even if there is no Article 5-type label. In the absence of U.S. troops stationed on the ground, options include commitments of air support, intelligence-sharing, and expedited arms aid if Ukraine is attacked. Indeed, Trump has said the United States would “certainly help… especially by air” if needed, while keeping “boots off the ground.” The viability of an Article 5-like pact ultimately depends on Western political will. Critics note that, so far, the notion has been “so vague it’s very hard to take seriously.” A pact would also likely require congressional approval in the United States, which is uncertain. Nonetheless, this path—a coalition security guarantee—is being actively pursued in the West as the most likely compromise to protect Ukraine in the absence of NATO membership.

- “Armed Non-Alignment” and Multilateral Support

Another approach would be to fortify Ukraine militarily without a formal alliance or binding guarantees of common defense, essentially turning Ukraine into a heavily armed non-aligned state. Advocates of this “porcupine strategy” argue that if Ukraine cannot enter NATO or receive strong, binding collective defense guarantees from a group of willing states, the West must ensure it has the weapons, training, and economic support to defend itself on its own. This model is often compared to the situation of Israel, which is not in NATO but enjoys massive U.S. military aid and a legal U.S. commitment to maintain its qualitative military edge. A non-aligned Ukraine could be similarly endowed with advanced Western arms and a long-term aid framework so that it is able to deter Russia through sheer military strength.

Western officials have floated ideas of making Ukraine a “military porcupine” since 2023. According to this approach, no limits can be placed on Ukrainian armed forces in terms of Western assistance and partnerships. Practically, armed non-alignment would mean continued deliveries of state-of-the-art weapons, high readiness, and possibly forward-positioned materiel for Ukraine’s use and significant financial assistance to ensure Ukraine maintains an adequate military force. The Coalition of the Willing’s current plans in fact include ongoing training missions, logistics support, air surveillance, and naval security operations to strengthen Ukraine’s defenses even in the absence of a treaty.

The upside of this approach is that it avoids a direct security guarantee that could escalate tensions or entangle allies in a war; instead, it focuses on enabling Ukraine to deter and defeat aggression on its own. But the drawbacks are significant. Ukraine would still lack an automatic tripwire to bring allies to its defense if overwhelmed. And sustaining “almost unlimited” military aid requires donor appetite, which could wane over time. Armed non-alignment also carries the moral hazard of Ukraine facing Russia largely alone if things go wrong. Bolstering Ukraine’s self-defense is a necessary step and better than nothing, but without a credible multilateral pact, Ukraine’s safety will precariously hinge on the strength of its own army and the support of partners. Total military aid to Ukraine from February 24, 2022, to October 2025 has already reached an estimated €110–120 billion based on the commitments from all donors. That’s approximately €30 billion per year. While the figure will be lower in peacetime, it will likely be at least €10 billion over a period of up to 10 years.

- Neutrality with International Security Guarantee

There is another alternative, albeit one that Europe and Ukraine are avoiding, even though it was floated early on in the war: Ukrainian neutrality backed by international guarantors. The difference between non-aligned and neutral status is that non-aligned status allows not only for the possibility of arming oneself and purchasing weapons from other countries, but also for the possibility of concluding military alliances and mutual defense pacts with other countries. This is a highly flexible and variable political strategy for a given state in the sphere of foreign policy and security.

Neutral status prohibits neutral countries from attempting to enter into any military alliances with other countries or blocs of countries, but does not impose any restrictions on self-armament, economic cooperation, military procurement, or receiving assistance from other countries, provided they do not have a formal presence in the neutral country. Furthermore, neutrality, unlike non-alignment, is a stricter and more stable international legal category—a status—that is, it is granted to a country by international organizations or groups of countries. In the case of Ukraine, such a decision—recognizing Ukraine as a neutral country and providing security guarantees for it—could be made by the United Nations Security Council.

It is precisely this alternative that Ukraine and Russia came close to agreeing on during the Istanbul talks in 2022. Kyiv signaled willingness to adopt “permanent neutrality” (no alliances, no foreign bases) if it received ironclad security guarantees. Article 5 of the Istanbul Communiqué, titled “Treaty on Permanent Neutrality and Security Guarantees of Ukraine” stated:

In the event of an armed attack on Ukraine, each of the Guarantor States, after holding urgent and immediate consultations…will provide (in response to and on the basis of an official request from Ukraine) assistance to Ukraine, as a permanently neutral state under attack, by immediately taking such individual or joint action as may be necessary, including closing the airspace over Ukraine, the provision of the necessary weapons, using armed force in order to restore and subsequently maintain the security of Ukraine as a permanently neutral state.

Ukraine understands that neutrality alone is worthless without enforcement and asked for a pact enforced by the militaries of major powers, naming the United States, United Kingdom, Turkey, Poland, Israel, and others as potential guarantors. A neutral Ukraine would need guarantors ready to fight a violator, akin to the guarantees given by Great Britain, France, Austria, Prussia, and Russia to Switzerland in 1815 in the form of permanent and armed neutrality or to Belgium in 1839–1914.

There are practical and moral risks, however. Who will be the guarantors? Will Russia be among them? Are security guarantees for Ukraine even possible without Moscow? Even if Western powers guarantee Ukraine’s neutrality, there is still the risk of a war with Russia—the very scenario Western leaders are trying to avoid. Moreover, Ukrainian society today is extremely skeptical of neutrality after experiencing aggression. Polls show strong support for NATO membership instead. Neutrality only guarantees security if all parties agree to respect it and ensure its observance.

In short, armed neutrality requires agreement between geopolitical adversaries—the West and Russia—which is difficult to achieve. At the same time, it truly is a compromise between the parties in which each side would have some gains and some losses. Ukraine would retain its sovereignty, and the geopolitical situation in Eastern Europe would partially return to its baseline before the start of the current confrontation between the West and Russia. Incidentally, Ukraine’s desire to become neutral was already enshrined in the Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine of July 16, 1990, which became the legal basis for the country’s declaration of independence in 1991.

Security Guarantees for Ukraine: A Strategic Dilemma for the Global Order

In practice, a solution could involve a multipronged approach invoking a combination of the above measures. Still, the prospects for establishing a stable, lasting peace are bleak unless Ukraine’s historical geopolitical challenges are addressed. For Ukraine, the concept of security guarantees is a double-edged sword: a tempting promise backed by bitter experience. The Budapest Memorandum taught Kyiv that ambiguous guarantees without enforcement are a sure path to disaster. Any new guarantee, whether a mere political statement or an unratified promise, risks repeating this tragic episode. Only those guarantees backed by real capabilities and resolve have proven effective. Ukraine’s sovereignty and European stability thus depend on a transition to real, enforceable security guarantees. In the current geopolitical climate, the United States and Europe appear ready to provide long-term support, but the form of this support and its formalization in a treaty is the next obstacle.

For any guarantor, however, security guarantees for a bordering or adjacent country entail the risk of being drawn into war in the near future. Troops stationed at an outpost will inevitably encounter the enemy at some point. Historically, this has happened many times. Therefore, Ukraine is unlikely to receive real military security guarantees—only assurances and promises of assistance are possible. But even if it received these from one side without the consent of the other, it would bring no good to either the country or its people. And, from an even more global perspective, the issue cannot be resolved in isolation from the issue of security guarantees for United States, Europe, and the Russian Federation.

Ukraine needs to recognize its place in the world and understand that its involvement in any military or economic bloc—whether Western or Eastern—turns the country into a border state and triggers a new round of struggle for control over. Indeed, paradoxically, all previous security guarantees for Ukraine, especially the bilateral ones, have in no way guaranteed Ukraine’s security. Instead, they served as a pretext for exacerbating international confrontation and drawing it into yet another war. Furthermore, given Ukraine’s location, none of the guarantors are capable of fully fulfilling their obligations to Ukraine and guaranteeing absolute protection in the event of a new conflict.

Providing security guarantees to Ukraine is not only a matter of military strategy but also a fundamental geopolitical dilemma for the potential guarantors. The problem stems from a combination of three factors: Ukraine’s geographic vulnerability, its political and economic weight, and its social heterogeneity. Together, these factors create a situation in which any attempt to integrate Ukraine into a collective security system or bilateral alliance becomes a titanic undertaking and a long-term challenge to the architecture of international stability.

First, Ukraine lies on the border between Asia and Europe, the border between Russia and the Western world. It is geographically exposed to both continents, unprotected by significant natural barriers, except for the Dnieper River and the Carpathian Mountains on its western borders. Ukraine’s vast steppes have historically been a hub for trade caravans and invading armies seeking to reach Europe. Its location on the frontier of Western and Eastern civilizations, which is perhaps where the country’s name comes from, makes the provision of security guarantees a high risk undertaking for both sides, as it not just a local issue but also a matter of strategic confrontation between the West and Russia. By defending Ukraine, guarantors may be drawn into a long war over the retention of a borderland that has historically served as an arena for invasions and wars. Its location, however, does also have benefits: It allows for better protection of the core of the metropolis by creating distance between dangerous neighbors, as well as access to important natural resources. Kissinger warned that Ukraine should not become one’s outpost against another, but a bridge between them: “If Ukraine is to survive and thrive, it must not be either side’s outpost against the other—it should function as a bridge between them.”

Second, Ukraine is too large to be seamlessly integrated into any system in the West or the East. Ukraine has a population of approximately 38 million according to UN estimates for 2024 and an area of approximately 600,000 square kilometers, around 115,000 square kilometers of which is now under Russian occupation. Its socioeconomic weight is comparable to that of the largest European countries. Ukraine is thus too large to be easily absorbed by any geopolitical player, even if it is becoming smaller. Its formal or informal inclusion in the Western world or a close alliance with Russia would not only alter the internal balance of power but also restructure the very logic of these entities. The history of Ukraine’s numerous partitions confirms that it was precisely its size and location that prevented it from becoming a permanent part of any single empire or bloc. It only fully acquired its internationally recognized territory in 1954, the year in which Crimea was transferred to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR), and has existed as a formally independent state for only about 35 years. However, dividing Ukraine into formal or informal zones of influence is also not a solution, as it would bring the militaries of the adversaries—Russia and the West—physically closer. Domestic demands for restoring Ukraine’s unity, coupled with the unstable geopolitical situation worldwide, would bring the risk of a direct clash between the two sides.

Figure 2. Map highlighting the approximately 115,000 square kilometers of Ukrainian territory under Russian occupation as of September 2025, which amounts to more than 19% of Ukraine’ s total territory. Source: DeepStateMap.live

Third, Ukraine’s sociocultural heterogeneity makes its inclusion in a unified project even more risky. Ukrainian society, the urban culture of which is still, to a large extent, a legacy of the Soviet Union and previous empires, contains supporters and opponents of all views. Unfortunately, a census has not been conducted in Ukraine since 2001, and sociological data is questionable. The data from the last full census 20 years ago, however, suggests that Ukraine’s sociocultural landscape is a patchwork: It shows a multiethnic state (77.8 percent Ukrainian, 17.3 percent Russian, and recognized minorities including Crimean Tatars, Romanians, Hungarians, Bulgarians, etc.) and a split-language landscape (Ukrainian is the mother tongue for 67.5 percent of residents and Russian for 29.6 percent). Urbanization sits roughly at two-thirds of the population, with wartime displacement adding at least 3.5 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) to the mix. Internal fault lines continue to exist and manifest themselves in collaborationism, regional differences, and a diversity of historical identities. Even now, amidst the war, despite the supposedly declared social unity of Ukrainians, the ease with which state structures of governance, security, culture, and humanitarian affairs in the occupied regions of southern Ukraine (and previously Crimea) have defected to Russia and the number of people detained in Ukraine on charges of aiding Russia speak to the persistence of deep-seated divisions. With integration, guarantor states would face the risk of importing Ukraine’s internal conflicts into their own systems. Ukraine could thus become both an ally and a source of persistent political instability.

Taken together, these factors create a unique situation: Ukraine is simultaneously too strategically important to ignore and too problematic to be easily integrated into any security or socioeconomic system. Security guarantees for Ukraine are not so much a matter of technical agreements or the signing of yet another set of documents, but, above all, the willingness of guarantor states to assume long-term geopolitical responsibility for the “borderland of civilizations” and be capable of devoting significant resources and making sacrifices for this purpose. This means not only defending Ukraine, but also a readiness for direct confrontation with an adversary over Ukraine, a redistribution of resources within one’s own alliances, and a willingness to manage the social and political complexity of Ukrainian society. It seems unlikely that any major powers would possess this willingness.

Security guarantees for Ukraine are thus becoming a strategic dilemma for the global order. Providing guarantees could expand collective security between the West and the East but threatens to accelerate its erosion if poorly implemented. At the same time, refusing to settle the war with security guarantees increases the risk of not only a protracted and destabilizing conflict but also its spread throughout Eurasia and beyond. Ukraine remains a “geopolitical pivot,” a term Zbigniew Brzezinski used to describe states whose importance derives not from their power but their location and geopolitical vulnerability. Its fate determines not only the balance of power in Eastern Europe but also the very stability of the global security system.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Ukraine cannot realistically be fully integrated into either the East or the West. Ukraine also cannot be divided without creating global security risks. The level of mistrust between key players is so high that ignoring the Russo-Ukrainian war is also impossible, as it poses challenges and risks to global stability. At the same time, the West is not ready to fight for Ukraine, but Ukrainians seek security guarantees from the West and do not want to be with the East, which is ready to fight for Ukraine.

In this situation, there are essentially two realistic strategies left. The first is to wait for a change in the geopolitical situation or a change of power in Russia, the EU, the United States, and Ukraine, hoping that a future shift in the political situation will allow for a shift in the current balance. This strategy appears very attractive to the European elite, but it means sitting on a powder keg. The second is to finally honestly acknowledge Ukraine’s current geopolitical position and codify its international obligations and guarantees. After all, despite numerous political statements, legislation, and treaties, Ukraine has been and remains a non-aligned state throughout its current political history. Preserving Ukraine as a stable, neutral zone with guaranteed security and inviolability between the West and the East would not be a shameful defeat or merely a temporary solution, but a victory for common sense and a human-centered approach to ending this terrible and dangerous war. The choice of whether this borderland will be a geopolitical bridge or a fortress will be left to the Ukrainian people, in whose hands, with an internationally recognized neutral or non-aligned status, the future will be.

Guaranteeing Ukraine’s inviolability through security guarantees will not end competition over its territory, but it would bring Ukraine from the battlefield back into the political and economic mainstream. At the same time, neither the West nor Russia would feel defeated. The distance between the so-called Eurasian and Western blocs would be maintained across the entire territory of Ukraine, and no one would be bound by rigid obligations that could drag them into a new war for Ukraine in the future. Of course, this scenario would require international oversight and effective social and economic solutions that stabilize Ukrainian society and restore peace and a sense of confidence in the future. For Ukraine, the issue of security guarantees is not only external—a matter of preserving sovereignty and creating mechanisms to prevent new military incursions—but also internal and requires creating a new sociopolitical balance with strict legal mechanisms to maintain the functioning of society, a significant part of which is isolated from political processes, while others are armed to the teeth.