Perspective – Written by Philip Pilkington

The financial press has begun to realize that Romania is close to bankruptcy if it does not make painful adjustments to its economy. The Romanian economic situation might be even worse than it first appears. For half a decade, the country has been borrowing money to prop up living standards, and Western financial markets have been accommodating this overspending. With a fiscal crisis looming and the United States aiming to pull back from Europe, it is unlikely that Romania can sustain these inflated living standards, and the populist right wing may get the upper hand politically.

The optimism around the victory of Nicuşor Dan against the nationalist George Simion has proved short-lived. It is quickly becoming clear how badly the Romanian economy has been mismanaged, and the financial press is now highlighting that the country is on an economically unsustainable path. The Financial Times ran a headline recently stating that “Romania risks repeat of collapse with ‘essential’ austerity measures.” The article highlighted that similar austerity measures in 2012 led to the collapse of the government. Around the same time, the paper ran an interview with Dan, which focused on the challenges that the country faced and the fact that populists like Simion were “waiting in the wings.” The tone throughout the pro-Brussels financial media is that the victory of the populists is inevitable.

The economic situation in Romania might be even worse than is being reported in the now-skeptical financial press. Since the start of the war in Ukraine, the Romanian economy has become increasingly imbalanced. Romania’s leaders seem to have started propping up living standards in the hope that Romanians would remain supportive of the war policy. In 2023, Hungary saw its economy contract by 0.8%, but Romania saw its economy expand by 2.4%. In the same year, government expenditure in Hungary grew 3.3%, a high rate of growth reflective of the energy price subsidies that were required during the war. Romania, however, saw government expenditure grow 6.3%. It is possible that almost all of Romania’s high economic growth in 2023 was due to the government spending large amounts of money.

This has led to enormous fiscal deficits in Romania. These deficits are now running at around 9.3% of GDP—levels that are completely unfamiliar to most countries outside of a severe recession. Faced with a declining economy due to the war in neighboring Ukraine, the Romanian government massively increased spending on public sector salaries, unfunded pension payouts, defense, and infrastructure. It has now become clear to the rating agencies that this is completely unsustainable.

This spending comes at a time when the Romanian economy faces serious structural problems as the United States moves to shift its geopolitical priorities away from Europe. Many who have travelled in the Central and Eastern European region are puzzled by Romania’s surprisingly high per capita GDP. It may be in part due to flawed statistical measurement. But Romanian living standards also seem to be “subsidized” by Western countries. Since 2020, Romania has run current account deficits of over 7%. Deficits of these levels are typically associated with sub-Saharan African countries that are extremely reliant on foreign aid. Romania seems to be consuming vastly more goods than it produces, and other countries seem to be financing this.

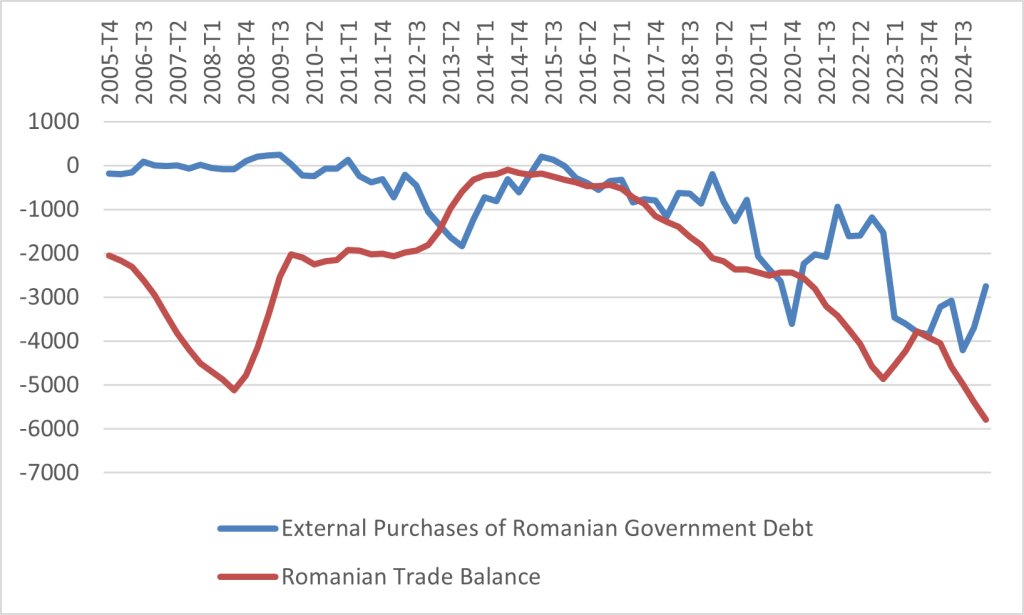

The following chart illustrates how Romania has been financing these enormous trade deficits. The chart shows that most of the Romanian trade deficits are being financed by tapping foreign borrowing markets to absorb Romanian government debt. Interestingly, prior to its previous crisis in 2012, Romania was running similarly large trade deficits. But as we can see from the chart, these were not financed by the issuance of large amounts of external debt. They were financed using inward foreign direct investment (FDI). While it is not ideal to finance huge trade deficits through FDI, it is certainly more stable than financing it with extensive foreign borrowing.

Source: Eurostat

Romania’s indebted and imbalanced economy seems to have undergone two phases. In the first phase, during the mid-2000s, the country leveraged its position as a close NATO ally of the United States and Europe to attract FDI that allowed it to live beyond its means. This phase reached a crisis point in 2012, after which Romania tried to rein in its overspending. The second phase began around 2020, when the country started issuing enormous amounts of debt abroad. There are good reasons to think that this arrangement is far less stable than the previous FDI-based borrowing. It also leaves open the question: will Romania be as attractive to foreign borrowing markets when the United States starts to retreat from its position in Europe and pivots to other theatres?

Romania may see its inflated living standards adjust significantly in the coming years. We may already be seeing the beginning of this adjustment. In July, the inflation rate shot up to 7.8% from 5.7% in June (for comparison, Hungary’s inflation rate was 4.3% in July). The core driver of this extremely high rate of inflation was the removal of electricity price caps, which the government can no longer afford. Electricity prices for Romanians rose 62% in July compared to the previous month, which will be felt by Romanian consumers, who could see their living standards decline as a result. These large price increases are expected to continue because the new government has raised VAT and excise duties, leading to inflation projections as high as 9.3% by the end of 2025. Rates of inflation this high could impact the value of the Romanian leu, which would further drive down living standards. Romania is likely at the beginning of a painful period of adjustment.

This adjustment in living standards could result in political destabilization. The rise of Georgescu and then of Simion shows that even with an economy with inflated living standards, Romanian voters were becoming agitated. They could become far more agitated if the living standards that they have become used to decline. If this happens, populist forces could gain an upper hand—especially in the short run. When they form a government, however, these forces would quickly find that they have no means to solve the country’s deep economic problems and may pivot to more primitive forms of nationalism.

The full analysis is available here.