How International Agreement Could Resolve Economic Imbalances

Connectivity Project by Philip Pilkington

Until recently it was widely accepted that protectionist policies in the 1930s contributed to the Great Depression and the geopolitical turmoil of the era. Historians and economists both largely agree on this issue and many scholars assumed the matter was settled. The lesson to be taken from this period was simple: tariffs and protectionism should never be seen as a replacement for constructive economic policy, and they should never, ever be imposed on other countries to engage in great power competition. The fact that we can see these trends emerge all around us today and many educated people accept them as normal is nothing short of shocking.

But even beyond the noxious historical trends a wave of protectionism might set off, there is also the simple fact that it is highly unlikely to achieve its goals. Historians and economists widely agree that while the protectionism of the 1930s did not cause the Great Depression, it likely exacerbated it. Yet, if we look at the protectionist schemes today, they seem even less credible than those of the 1930s. This is because in the 1930s, the countries that pulled up the tariff drawbridges had largescale industries to protect. Today the advocates of protectionism, concentrated as they are in countries that have largely deindustrialized, seem to think that tariffs will cause these industries to reappear. This is very close to magical thinking. While it is true that, in theory, if a country like the United States were shut off from all world trade it would eventually be forced to reestablish its own domestic industry, it seems highly likely that the country would simply collapse into extreme inflation long before this occurred. The United States today already faces problems with structural inflation, yet policymakers do not seem to grasp that their protectionist policies are one of the key drivers of this structural inflationary tendency in the economy.

There is also the question of which countries owe money and which lend it. Much of the debate around protection today, especially in the United States, seems to rest on the implicit assumption that America is economically powerful enough not just to shut down large swathes of global trade but also to hobble the economic development of its rivals. Even a cursory examination of the data reveals this to be a dangerous fantasy: America is a country that is massively in debt to its trading partners and its living standards are effectively propped up by issuing financial assets to other countries in exchange for goods and services. In a world where trade and capital flows were restricted, the United States would have to adjust to a far lower standard of living. It feels that all of this was widely appreciated until about a decade ago, when hysteria started to set in amongst the Western elite.

Yet despite this descent into self-destructive protectionism being deeply misguided, it is responding to a very real problem. For the past 30 years, the Western economies – led by the United States – have let globalization rip. This has resulted in deindustrialization in Western economies and the buildup of enormous trade imbalances. Now that we face epochal shifts in the world system, these imbalances need to be rectified, or the consequences could be catastrophic for the weaker economies that find themselves indebted.

In this paper we evaluate a long-forgotten proposal for an International Currency Union, first articulated by the economist John Maynard Keynes at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944. I will argue that the hurdles to this system were always political, but now that the balance of power in the world is shifting dramatically, it could be a more fitting solution to current global imbalances. Doing so could place the world economy on a new, more stable footing. In what follows, I evaluate what a New Bretton Woods could look like, for a twenty-first century that looks like it will be multipolar.

Global Imbalances in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

Since the era of globalization took off in the 1990s, the volume of global trade has exploded. In 1990, global trade made up just under 38 percent of global GDP. By 2022, this number had risen to almost 63 percent. This process of globalization has fundamentally altered the world economy and given rise to an enormous explosion of increased prosperity. In 1990 just over 38 percent of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty – meaning that they lived on less than $2.15 per day – but by 2022 this number had fallen to just under 9 percent. There is little doubt that globalization has proven to be an enormous boon for most of humanity.

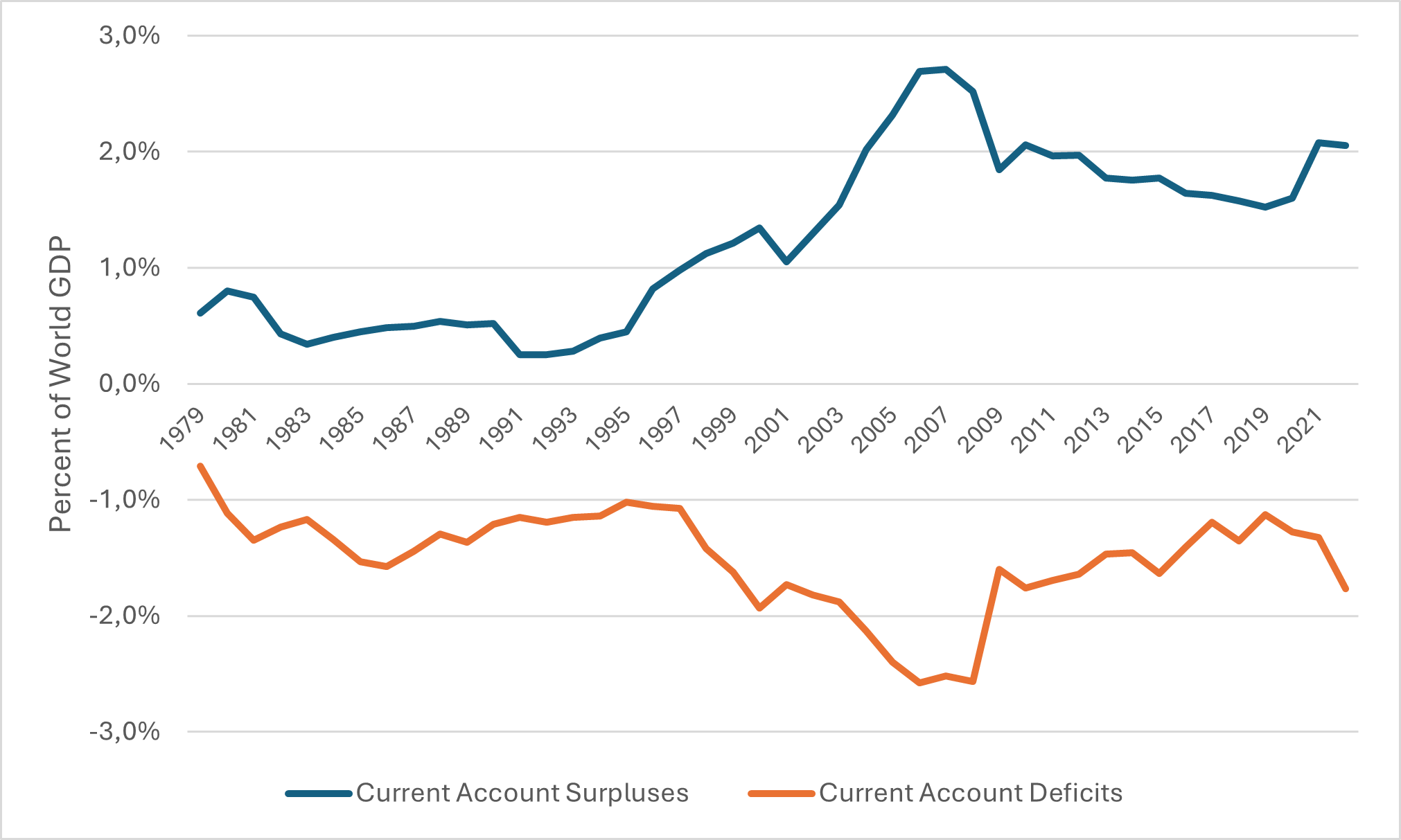

Yet it would be naïve to paint a picture of globalization as a magical process with only upsides. The era of globalization has given rise to enormous imbalances in the world economy. It has led to the deindustrialization of many of the Western developed nations and unleashed chaotic capital flows that generate financial crises with relative regularity. At the heart of these developments, however, are trade imbalances. Ultimately it is trade imbalances drive the processes behind crises associated with free capital flows, and ultimately trade imbalances are also the main cause of deindustrialization. The following chart shows global current account surpluses and deficits expressed as a percent of world GDP.

Here we see the impact of globalization very clearly. Prior to the 1990s, global imbalances never reached over 1.5 percent of global GDP. But as globalization set in, we saw global imbalances rise to well over 2.5 percent of global GDP. Today they have come down somewhat, but they remain quite high – probably around 2 percent of global GDP or so.

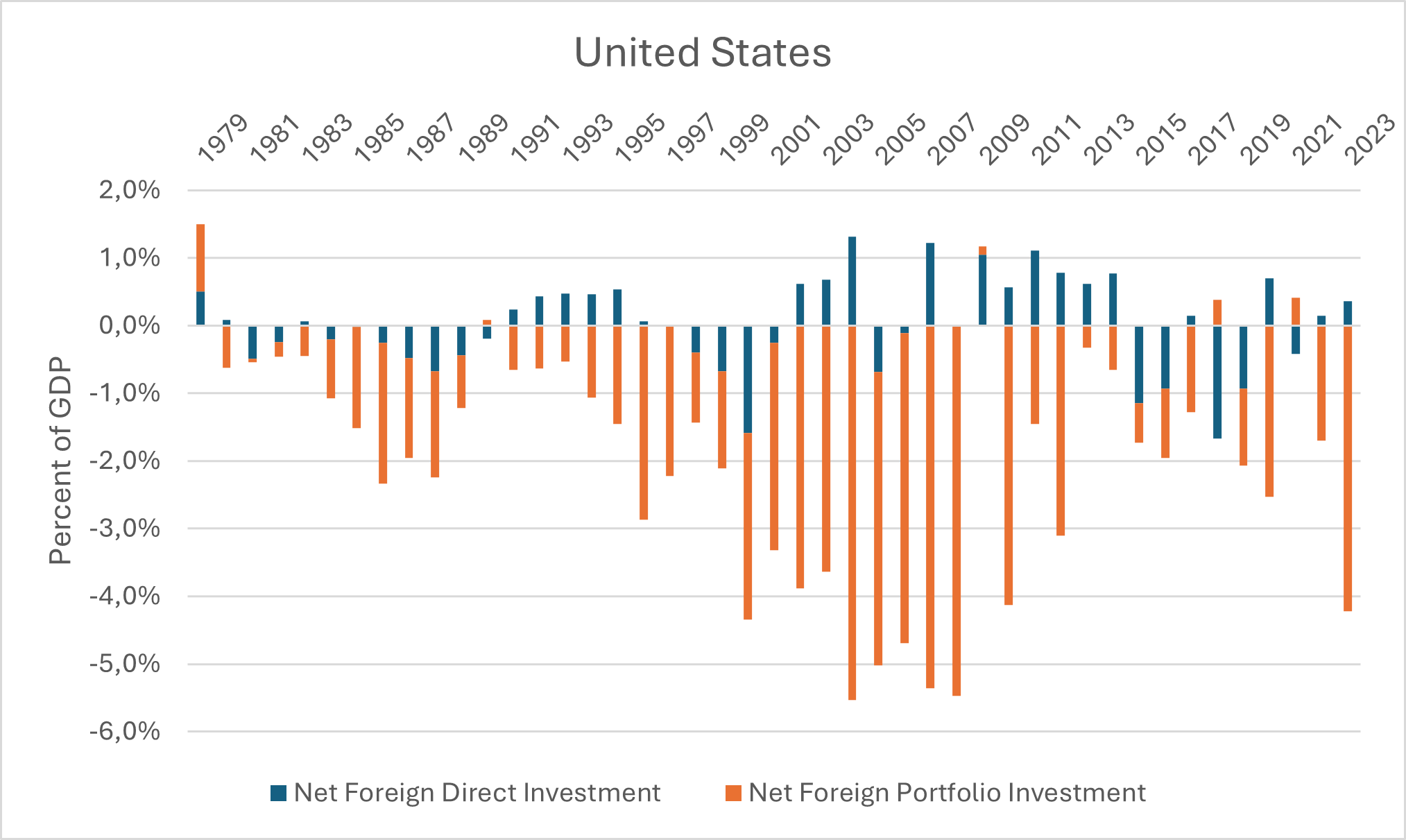

These current accounts have been supported by enormous capital flows. Increasingly, these capital flows have not consisted of foreign direct investment but rather of portfolio investment. Foreign direct investment tends to be highly beneficial to a country. It is a stable source of inward investment and builds productive assets in the country it enters. Portfolio investment, on the other hand, is simply agents from one country buying financial assets from another country and in doing so allowing them to run trade deficits. These portfolio flows give rise to problematic global imbalances that bring with them the problems already discussed. Typical in this regard is the United States. The chart below shows net flows of foreign direct investment and foreign portfolio investment into the United States.

As we can see, it is mainly its foreign portfolio investment that allows the United States to run an imbalance on its current account. In effect, these portfolio inflows artificially prop up the dollar and cause the United States to run large trade deficits. These trade deficits cause problems with America’s industrial base and are increasingly the focus of policymakers today. In effect, these portfolio inflows show the basis on which the United States has become a country reliant for its living standards on convincing foreigners to send real goods and services in exchange for paper assets.

The Opening for a New Multipolar World Economy

The problem with international monetary reform has always been the politics surrounding it. International monetary reform requires international institutions, and international institutions require buy-in from a large part of the global community. In practice, international institutions have proved less effective than some might like because of this problem. This has led some to call into question the efficacy of international institutions and promote solutions being formulated at a national level, with international problems being approached on a pragmatic bilateral or multilateral basis.

Yet due to the nature of the problems of money and trade, it has long been known that international institutions are required. In fact, of all the international institutions that were created in the twentieth century, the institutions dealing with issues of money and trade have proved most effective. While there are many criticisms that could be levelled at the institutions that were born out of Bretton Woods – most notably, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – few would criticize them for being toothless. Since their creation they have proved themselves critical to the global economic architecture – especially during crises.

There are two reasons for this. The first is the nature of the institution itself – and the problems that it addresses. In a case that involves, for example, an international court, a nation can at the extreme ignore the judgement of the court. Because the international court has no military or police power, it cannot enforce its ruling and ultimately requires the goodwill of those who recognize the authority of the court – goodwill that it is assumed might start to breakdown in a situation where a court issues a harsh ruling against a nation state. Issues dealing with money and trade do not face this problem in as extreme a manner because they inherently have coercive power over those they govern. A country that is partaking in an IMF lending program that wants to ignore the IMF will soon find that its access to IMF loans has dried up, and they may face a serious economic crisis. The IMF and similar institutions may not possess the full police and military power of a nation state, but it does possess the power of the creditor.

The second reason that international institutions dealing with money and trade have proven powerful is that they are widely seen as being primarily backed by a major global power: the United States. The reasons for this are historical, and they are crucial to understand when thinking about how to rebalance the global economy. At the original Bretton Woods conference in 1944, a host of different proposals were put on the table. Most of the initial proposals were conceived by either economists or financial experts and so were geared towards maximum functionality. But as the conference wore on, the proposals were watered down dramatically in line with power politics. The most indicative in this regard were the proposals of Keynes, who was also the chief negotiation of Great Britain at the conference. Keynes’ proposal, which we will suggest could be crucial to solving the problems of trade imbalances today, was structured in such a way that it would seek to resolve the trade imbalances that Keynes and others saw as having led to the turmoil of the interwar years. But because the proposal was designed to apply pressure to both creditors and debtors in the global system in equal measures, it was seen by creditor countries as special pleading from a debtor country, Keynes’ Britain, to a creditor country, the United States.

Any international institution that seeks to resolve the global monetary and trade imbalance problems in the global economy will always inevitably encounter this problem. These problems are at their heart creditor-debtor relationships and the solutions tend to undermine the power that the creditor can wield over the debtor. Since global political disputes are usually dictated in line with the relative power of a given nation, this means that creditor nations are usually extremely reluctant to give up the power that they possess as creditors. As we have already seen, this can prove very short-sighted as the dynamics of creditors and debtors in the global economy can shift dramatically. The United States opposed the more equitable plan put forward by Keynes because they were in the position of creditor after the Second World War. But today the country is one of the largest debtor nations in the world – and this indebtedness is mirrored in the deindustrialization that the country has experienced. If the American delegates had accepted Keynes’ solution in 1944, the United States’ deindustrialization and fall into debt would likely never have happened.

What was accepted in Bretton Woods in 1944 was therefore a compromise solution. The American delegation realized that some international reform was required so that the instabilities of the interwar period were not repeated, but they wanted to maintain the power that they possessed emerging out of the Second World War as the major creditor nation. The compromise solution was the Bretton Woods system. The system worked by pegging the U.S. dollar to gold at a fixed rate and then pegging the currencies of all the other participating countries to the U.S. dollar. This meant that every currency participating country was in theory pegged to gold, but only through the U.S. dollar. But it also meant that most global trade would tend to be dollar-based because the dollar, rather than gold itself, would be the standard numeraire for international transactions. Thus, out of the Bretton Woods system was born the dollar standard that has existed since the war. The IMF and the World Bank were added as supplements to this dollar-based system. Their role was to help countries that experienced crises when trying to maintain their adherence to the Bretton Woods system.

The current fiat dollar system that has given rise to such profound imbalances in the global economy evolved naturally out of the inevitable breakdown of the Bretton Woods system. The breakdown of the Bretton Woods system was inevitable for two interrelated reasons. Firstly, it required that the United States run a balanced trade account. If America had run trade surpluses for too long, it would have removed dollar liquidity from the global system and disrupted global trade. If it had run trade deficits for too long, other countries could make claims on American gold reserves and the dollar would lose its backing. Secondly, the system provided an inbuilt temptation for the United States to run trade deficits. This is because they could be confident that, in the short-term at least, dollars would be accepted for international payments for goods and services. During the Vietnam War, the United States succumbed to this temptation and started to run consistent trade deficits so that it could wage war in Southeast Asia while simultaneously running high consumption policies at home – the ‘Great Society’ program of President Lyndon Johnson. These policies soon made America’s partners nervous of the status of the dollar. In August 1971, the French government under President Georges Pompidou dispatched a French naval vessel to New York to request a large shipment of gold to be moved from America to France. That same month, President Richard Nixon realized that the United States did not have sufficient gold to meet their liabilities and closed the gold window. From this moment on the U.S. dollar would be a purely fiat currency – a fiat currency being in effect a paper currency that is only backed by the credibility of the state issuing it.

Since there were no alternatives to the dollar, the world continued to use it as it had before. But since there were no constraints on the creation of dollars, America could now flood the world with a potentially limitless amount of dollars – provided the world accepted them. This is why the global imbalances have gotten more extreme over time. Developing countries are incentivized to run export-led growth models to accumulate dollar reserves and insulate themselves from crises. This growth model has been actively encouraged by the Bretton Woods era institutions like the IMF to develop economically without falling into debt. The desire to accumulate dollar reserves raises the value of the dollar above what it would be if that demand were simply driven by American imports and exports. This in turn gives rise to a demand for American financial instruments – mostly stocks and bonds – as these are seen as somewhere to park these dollar reserves while allowing them to accumulate value through time. Meanwhile, the United States accumulates ever more foreign debt. It is out of these self-destructive dynamics that there are now reasons to think that the geopolitical environment has shifted in such a way that a discussion of a more equitable international framework for monetary and trade matters might be possible. Here three relevant factors stand out.

The first is the fall of the United States into a terminal debtor position in this system. The United States has now been running current account deficits in most years since 1983, and it has generated consistent current account deficits without interruption since 1991. The United States now has an overall foreign debt load of just over 70 percent of GDP, the fifth largest in the world after only Spain, Portugal, Greece, and Cyprus – all countries whose membership in the Eurozone allows them to maintain such large burdens. The only reason that America has been able to shoulder this enormous debt burden is because of the artificial demand for the dollar inherent in the post-Bretton Woods arrangement. If this demand were not present, the U.S. dollar would have adjusted long ago to rebalance American exports and imports – and in doing so would have mitigated the brutal deindustrialization that the country has suffered. Today, American policymakers and voters are highly sensitive to these problems and solutions are being discussed. But all these solutions seem to revolve around waging trade wars. While the current system of dollar hegemony is extremely self-destructive for the United States, it is nothing in comparison to what would happen to the country in the event of a serious trade war. As we have shown in a previous paper, the United States is now heavily dependent on imports to maintain basic supply chains. Without these imports, many of which come from countries like China, the American economy would grind to a halt and would experience extremely high inflation – up to and including hyperinflation. This means that if American policymakers are rational, they should come to realize that a far better solution to these problems would be an international institution that seeks to rebalance global trade and monetary flows.

The second relevant factor is the position that China finds itself in. China is today where the United States was in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War: it is the largest manufacturer in the world and, due to this, is the world’s third largest creditor nation after Japan and Germany. But the economy that China has the most claims on – the United States – is, in a sense, too big to fail. Compare the Chinese-American relationship today with the American-British relationship in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War as Britain was the largest debtor vis-à-vis the United States at the time. Today Chinese exports to the United States make up around 2.8 percent of Chinese GDP. By contrast, in 1950 American exports to Britain made up around 0.4 percent of total American GDP. The United States could have seen the British economy collapse under a foreign exchange crisis with little impact on the American economy. Indeed, in 1956 during the Suez Crisis, the United States threatened to dump sterling debt which shows this was very much so understood at the time. While the Chinese economy would no doubt survive the collapse of the U.S. dollar and the American economy spiraling into uncontrollable inflation, it would not be beneficial for China. It might also trigger severe geopolitical instability that would be detrimental to Chinese interests.

This unique set of circumstances means that, even though China is clearly in the position of creditor vis-à-vis the United States, it is nevertheless strongly in its self-interest to both move to a more balanced global growth model and ensure that this happens with minimal disruption. There is a strong case to be made to the Chinese that they should back an international institution to gradually wind down global imbalances so that the world can move toward a stable, peaceful model of mutually beneficial trade and development. China has clearly signaled that they want to see a new world order based on equity and national sovereignty. In accepting that they would gradually renege their creditor position on the world stage over time, the Chinese could display the enlightened global leadership needed to peacefully transition away from the post-Bretton Woods paper dollar model of global trade.

The third relevant factor are the dramatic and rapid changes that have taken place in the global economy since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Since the start of the war, changes have taken place that seriously threaten the post-Bretton Woods system. We are already seeing the rise of alternative currencies in the settlement of bilateral trade. The most notable here is the case of Russia, where only around 30 percent of its trade is undertaken in Western currencies at the time of writing. We are also seeing a rush for non-Western central banks to buy up gold bullion. This development has been triggered by the extremely risky decision taken by the U.S. Treasury to seize the foreign exchange reserves of the Russian central bank and, in doing so, endanger the credibility of the U.S. dollar as a nonpoliticized, reliable reserve currency. All these developments are currently formless. Many countries know that they want to move away from the dollar standard, but they are not quite sure what they might move to. There are hints that the BRICS might launch a currency, for example, but no one knows what this might look like.

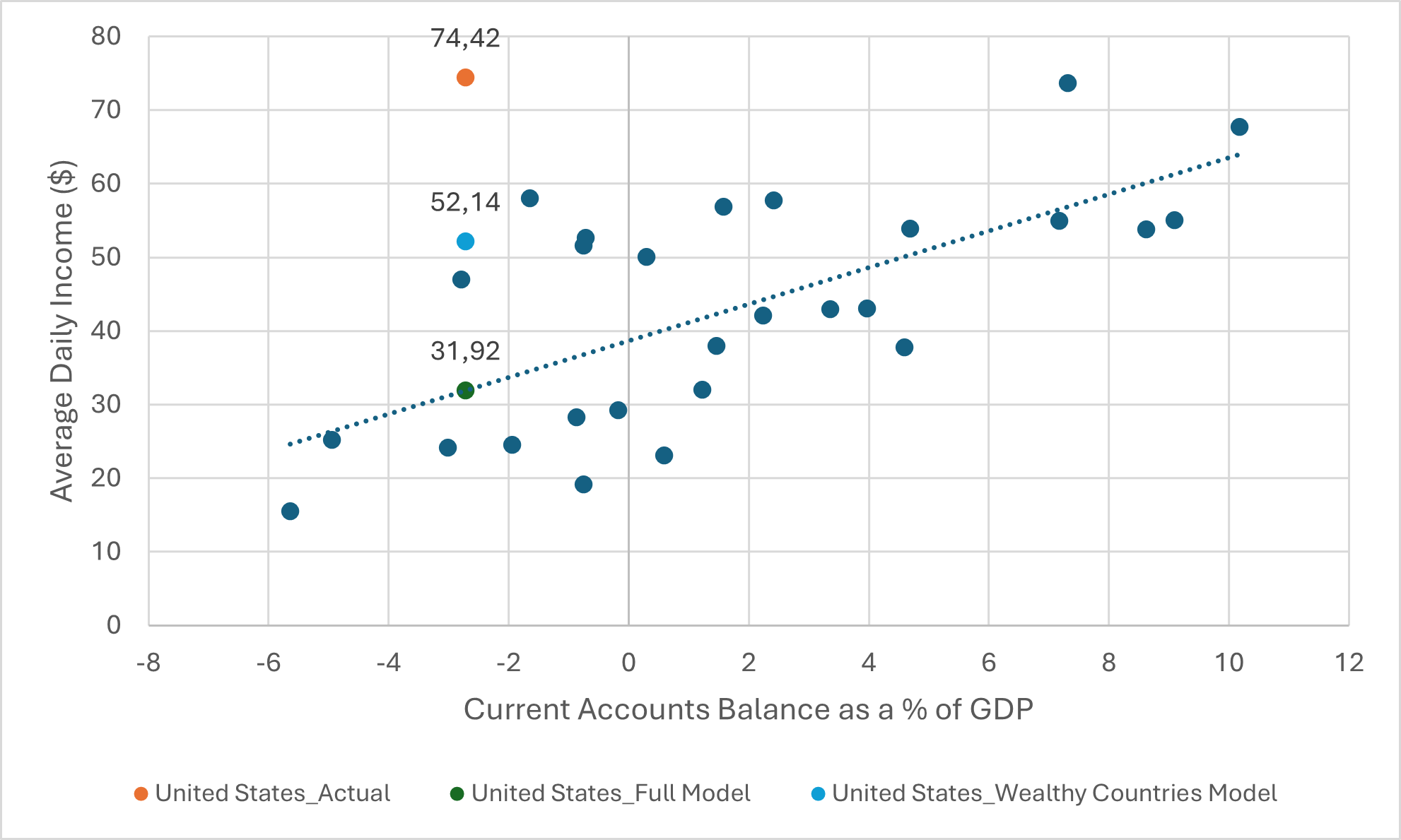

This situation puts pressure on both the United States and China. For the United States, the writing should be on the wall: the era of U.S. dollar hegemony is coming to an end. If the United States mismanages the transition away from the U.S. dollar standard, it faces a potentially ruinous decline in living standards. The following chart shows average daily wages in U.S. dollars plotted against current account balance for 27 countries. It shows that there is a strong correlation between the two. The country highlighted in orange is the United States and is a clear outlier. This outlier status is almost certainly generated by the fact that the U.S. dollar is the global reserve currency. The chart also shows that in the case that the privileged role the U.S. dollar possesses dissipates, American living standards would fall by 27 percent. This would manifest itself through a sharp decline in the value of the U.S. dollar and a painful rise in prices, particularly of imported goods. If this process happened overly rapidly, the United States could face serious social unrest.

China is on the flip side of this relationship. First, if the American current account deficit was forced to close by a rapidly declining dollar, the Chinese current account surplus would close too. This would greatly hamper Chinese growth in the short-term. The upward valuation of the renminbi in such a situation could also introduce instability into the Chinese monetary architecture. A collapsing dollar would require high interest rates in the United States and low interest rates in China, and such a circumstance would almost certainly give rise to chaotic capital flows. Finally, the potential for social instability in the United States should worry China in and of itself.

All of this suggests that it is strongly in the interests of both countries to come to the table and negotiate new multilateral international institutions that will support balance in global trade and monetary affairs. Such a meeting – call it a new Bretton Woods – would have the goal of ensuring that the current imbalances in the global economy do not result in sharp disruptions that could give rise to serious geopolitical instability. Both sides would lose something. The United States would have to admit that the era of dollar hegemony was over – but this is happening regardless. Meanwhile, China would have to commit to more balanced trade in the long-run and give up its current position as the leading global creditor. But as with the case of the United States after the Second World War, it could be unwise to assume that just because one can claim creditor status at the time of writing that this will be true in the future. Also, bellicose attitudes are being generated in the United States by China’s large trade surpluses, and addressing these diplomatically could be fruitful. Finally, in the long-term China needs to move toward domestic-focused growth and higher living standards, and a new Bretton Woods system could facilitate the transition to this model in a much more orderly fashion than would be achieved otherwise.

An International Currency Union for the Twenty-First Century

Since the politics have changed, we would suggest that Keynes’ bancor idea – adequately altered to take account of new findings in economics – should come into its own as the world system undergoes dramatic changes. Both the United States and China have vested interests in ensuring that the transition from the dollar-based global system to a new multilateral system goes as smoothly as possible. With the political hurdles effectively lifted, all that is required to stabilize the new world system is a coherent plan and the political will to create a sequel to the Bretton Woods conference.

Let us now turn to the basic structure of Keynes’ bancor plan. In the previous two sections we laid out the basic problem when it comes to global money and trade flows: imbalances. Despite what some free trade advocates would like to believe, trade imbalances are a problem as old as human history – and throughout human history they have been associated with war, strife, and conflict. Throughout human history, there has never really been a long-term solution to these imbalances. Gold standard systems, the default system that the world often reverts to, work – until they do not. The history of gold standard systems is one in which the gold standard works for a while and then breaks down under its own contradictions. Meanwhile the truly laissez-faire system of free-floating currencies and dollar hegemony works seamlessly, except insofar as it allows massive imbalances to build up in the global system that quite literally threaten world peace.

The reality is that trade imbalances are a political problem and so require a political solution. No matter how technical a system of trade intermediation may be, at heart it is fundamentally an international treaty. At a very basic level, all these proposals are complex arrangements that require all countries to accept them and adhere to them. The ‘rules’ that are set up, with their reference to deep layers of international trade and currency theory, are all at the end of the day international laws that countries recognize because they understand that recognizing them is both in their self-interest and the interest of other countries. In a strong sense, it is the agreement itself that is more important than any specific system design. That said, let us try our best to lay out a workable system here.

In a glorified – and probably mythic – time of international barter, there could be no imbalances. If one country traded cotton and the other traded wine, there could never be a surplus or a deficit. Wine was handed over, cotton was received – and vice versa. It is when money enters this relationship that the problems start – except of course, much like the Biblical Fall, trade cannot really be imagined without the intermediation of money. This is because when a trader carried large amount of goods from one place to another, he would not always find goods in the foreign location that were fit to barter. And so, money logically arises to facilitate trade – money that can be accepted for goods now and spent on goods later, say, when another trader visits the domestic location of the original trader. When money enters the picture so too do imbalances. One country might have more money than another and it might buy more wine than the other buys cotton. This means that one country goes into deficit on its balance of payments and the other goes into surplus. The deficit or the surplus can be seen on the accounts of each country. One account shows more money handed over for wine than was received for cotton – a deficit. The other account shows a surplus.

As trade relations evolve, these monetary transactions become claims – debts and claims, liabilities and assets. Trade credit allows one country to purchase goods from another and, via the banking system, issue debt to that country. A businessman in one country might order wine and send an IOU through the banking system for the wine to the producer. The country he resides in now ‘owes’ money to the country that he is purchasing the wine from through the banking system. Eventually these claims need to be settled in some sort of international clearing house. Under the gold standard, the settlement of such a claim is straightforward enough: one country simply ships the gold that they owe to the other. Under a fiat money system like the dollar regime, paper currency is sent instead – currency that is often recycled into financial assets in the country running the deficit. Now we see more clearly why the fiat dollar regime allows for enormous imbalances to build up: under the gold standard, at a certain point, the gold runs out and the trade deficit closes; under the fiat dollar system more dollars can be printed at will.

The bancor system seeks to avoid these imbalances without resorting to harsh discipline imposed by the gold standard. The bancor would operate as a supranational currency but would never be used directly. It would only be used to clear trade through a global bank, the International Clearing Bank (ICB) which itself was part of a broader organization, the International Currency Union (ICU). In the ICB, trade is cleared in bancors which are exchanged for each country’s own currency – so there is no reliance on the currency of a single country. Each country would get an initial allocation of bancor proportional to its total trade – Keynes proposed one half the total five-year average of exports plus imports. This allocation was called a country’s ‘index quota’. Each country’s currency is pegged to bancor, but the peg is adjustable in line with the rules of the system.

The basic idea to maintain balanced trade accounts is simple enough: countries that run imbalances are penalized for doing so. In the gold standard system, the country running the deficit is penalized and the country running the surplus is rewarded. But in the bancor system both sides are penalized. Limits are placed on both the accumulation of deficits and of surpluses. Linked to this, there are pressured and forced devaluation and revaluation clauses. If a country’s deficit runs at an annual average of 25 percent of its index quota, it is given the option to devalue its currency by up to 5 percent. If a country’s deficit runs at an annual average of 50 percent, it is designated as ‘supervised’ and is forced to devalue by 5 percent. The same pressure is placed on a country running persistent surpluses of 25 percent or 50 percent of their index quota, but they are first offered and then forced to revalue their currency by 5 percent. Interest was also charged on any imbalances to create more pressure on countries to solve their imbalances. The interest rate charged on both surpluses and deficits would scale given their relative size. 5 percent annual interest would be applied to a country running a deficit or surplus over 25 percent of their index quota and 10 percent would be applied to a country running a deficit or surplus over 50 percent of their index quota.

Finally, there was the issue of forced investment. Keynes intuited that sometimes devaluations and revaluations would not clear trade imbalances – or might not do so proportionately. In economics parlance, he recognized that the Marshall-Lerner conditions might not hold for all countries at all times. This intuition was confirmed in 1960 by two economists: Hendrik Houthhakker and Stephen Magee. The ‘Houthhakker-Magee effect’ as it has come to be known shows that in the United States the income elasticity of imports is roughly double the income elasticity of exports. This means that if the United States grows at roughly the same rate as the rest of the world it will tend to suck in more imports than the exports demanded by the rest of the world. This means it will tend to run trade deficits. Extreme variants of Houthhakker-Magee can lead to some countries engaged in perpetual devaluation while not seeing their trade balances improve – sometimes they even worsen. For example, since the late-1980s the United Kingdom has been running consistent and ever-worsening current account deficits. Yet in this period sterling has fallen from roughly $1.80 to around $1.25 versus the US dollar. This is where the need for forced reinvestment comes in. If a country engages in devaluation but does not see an improvement in its trade balance, the bancor system forces the countries that run trade surpluses with this country to recycle these surpluses into the country. This means that the surpluses are invested in the country that is running a trade deficit in the form of foreign direct investment.

The basic outline of the plan as laid out by Keynes is sound, but the numbers he used seem unworkable – and they have become more unworkable through time as global trade has expanded. The table below shows trade for the United States and the United Kingdom after the Second World War and today. They also include the index quotas based on Keynes’ original plan together with the points at which intervention is required. All of this is expressed as a percentage of GDP.

| United States | United Kingdom | |

| Exports and Imports as a % of GDP | ||

|

1947 |

10.6 | 37.0 |

|

2022 |

27.0 | 70.0 |

| Index Quota as a % GDP | ||

|

1947 |

5.3 | 18.5 |

|

2022 |

13.5 | 35.0 |

| 25% of Index Quota | ||

|

1947 |

1.3 | 4.6 |

|

2022 |

3.4 | 8.8 |

| 50% of Index Quota | ||

|

1947 |

2.7 | 9.3 |

|

2022 |

6.8 | 17.5 |

The first issue that stands out is that a country that has a much larger share of trade as a percentage of its economy will be able to run much larger trade surpluses or deficits than a country with a smaller trade share of GDP. It seems that Keynes should have scaled relative to GDP. The index quotas themselves also appear too large. For example, in 2022 Keynes’ system would have only forced a 5 percent devaluation of the U.S. dollar when America’s trade deficit hit 6.8 percent of GDP – an enormous trade deficit.

It seems like a better approach to the adjustment problem under the bancor is to simply consider current account surpluses and deficits as a percentage of GDP and force adjustments in line with these. This will provide a much simpler system of rules. Intuitively, if we strive for a system of balanced trade, we should allow a country to engage in devaluation or revaluation if their current account deficit or surplus crosses 0.75 percent of GDP. They should be forced to revalue if it crosses 1.5 percent of GDP. We should also impose some firm rules for forced investment. If a country maintains a current account deficit of over 1 percent of GDP despite two consecutive 5 percent devaluations, the countries that run trade surpluses with this country should be forced to invest the money back into the country in the form of foreign direct investment. The foreign direct investment should be channeled into infrastructure and development aimed at bolstering import substitution or export competitiveness.

| Current Account Imbalance as % of GDP | Devaluation/Revaluation | Interest Charged |

| 0.75% | 5% Optional | 5% |

| 1.50% | 5% Forced | 10% |

| 2.25% | 5% Forced + 5% Optional | 15% |

| 3.00% | 10% Forced | 20% |

The above table outlines the basic rules of the bancor system. These rules will continue to scale up to higher numbers, although under such a system a current account imbalance of more than 3 percent of GDP seems highly unlikely. It should be noted that the interest charged annually on the bancor accounts will be paid directly by the government of the country experiencing the imbalance. That is, it will be either paid by raising tax revenues or by government borrowing. This will provide a strong incentive for the authorities in the country in question to resolve the imbalance. These interest payments will be paid into a fund that can be handed over annually to international development banks, either those that currently exist like the World Bank and the New Development Bank, or a newly created entity in the ICU.

When it comes to excess surpluses, the country running them will always be given the option to recycle them voluntarily into the corresponding deficit countries either in the form of foreign direct investment or foreign aid. Of course, both the deficit and surplus countries will have to agree to this arrangement on a bilateral basis – it is as important that the deficit country accept the transfer as that the surplus country should offer them. If the country running the surplus can dispose of it in this way, they will incur no penalties and will require no devaluation. This caveat means that a country within the bancor system can in fact run a mercantilist growth policy that prioritizes large trade surpluses, but that country will have to counterbalance this with investment or consumption transfers to its trade partners.

Finally, there is the question of incumbent imbalances. As shown at the beginning of this paper, global trade imbalances have gotten larger in the past thirty years. If the new bancor system were imposed on the world system while these imbalances are still operative, it might lead to forced adjustments that were too rapid. For this reason, we propose that there should be a grace period where the rules are enforced less forcefully. For example, in the first eight years when the new system is imposed devaluations and revaluations should only be pushed on countries breaching the rules by 50 percent. So, a devaluation or revaluation would be allowed with a current account deficit or surplus of 1.125 percent and would be enforced with a current account deficit or surplus of 2.25 percent.

There is a separate institutional question of what happens to the current global monetary and financial institutions. Here we think not just of the remaining Bretton Woods institutions, but also the new BRICS institutions. The beauty of a new monetary architecture is that it could leave these institutions intact and absorb them. When the board of the new ICU is set up members of the older institutions can group together. They can even use the older institutions as conduits for distributing, for example, investment funds generated by the ICU. In fact, Keynes anticipated that like-minded countries or countries with strong historical ties might band together in international institutions. He thought that this would be highly complementary to his vision for the ICU, writing:

One view of the post-war world which I find sympathetic and attractive and fruitful of good consequences is that we should encourage small political and cultural units, combined into larger, and more or less closely knit, economic units. … Therefore, I would encourage customs unions and customs preferences covering groups of political and geographical units, and also currency unions, railway unions and the like. Thus, it would be preferable, if it were possible, that the members should, in some cases at least, be groups of countries rather than separate units.

This is a basic sketch of the system. It provides a basic outline of how it would work and what the basic thresholds would be. It does not answer every question. For example, since exchange rates will be controlled, the system obviously requires capital controls. This raises the question of whether any purely financial investment is allowed to cross borders or whether only foreign direct investment is allowed. There are no simple answers to issues such as these and ultimately a new monetary system will require extensive debate, negotiation, and design. This is beyond the scope of the present paper which merely seeks to lay out a renewed bancor proposal that would solve the problems facing the world economy today and prevent another chaotic and destructive slide into trade war.

The past few years have been ones in which global conflict has flared up in a manner that is more concerning than at any time since the end of the Second World War. Economists cannot offer solutions to all complex geopolitical problems, but they know that trade imbalances tend to vastly increase tensions between nations and make compromise on these non-economic topics more difficult. Due to the politics and economic structure of the time, the bancor was shelved in 1944. But due to the changes in the global economic system caused by aggressive globalization, there is a strong case to be made that its time has come. Implementing the bancor solution to world trade could provide a new constructive economic vision for a world economy that currently feels chaotic and unmoored. It could provide the keystone to global governance in the 21st century.